Even on a good day, we tend to think we’re pretty bad at finding our way around despite all the advantages of modern awareness technologies. But, “The Image of The City”, Kevin Lynch’s classic study on the social, cultural, and physical imprint that our places make on us, shows how adept we actually are at internal map-making.

In the 1960s Lynch conducted surveys, ethnographic interviews, and a form of participatory design to elicit the mental models that city dwellers develop over time and “hold” as they navigate their surroundings. He talked to people in three distinctly shaped cities: beginning on the East Coast in Jersey City and Boston, then moving on to Los Angeles. In each, he and his students approached pedestrians, asking them if they could draw their neighborhood from memory, then progressively larger parts of the city. And with each interview the images were continuously clear and accurate.

Lynch’s research produced one of the most seminal theories in modern urban planning: that a city is comprised of 5 elements that make an image in the minds of its inhabitants, growing in shape and detail the longer they live there and more they explore.

Paths

Streets, roads, and sidewalks that we use to navigate the city. For many people in the study, paths were the predominant elements in their image.

Edges

Edges are organizing features such as railroads or highways that delineate sections of a city.

Districts

Districts are areas that people enter “inside of” which are recognizable and have an identifiable character such as Dallas’ Deep Ellum or East LA.

Nodes

Nodes provide people with junctions, places of transition from one area to another. They are often a memorable convergence of paths.

Landmarks

Landmarks are identifiable “external” structures such as buildings, signs, and natural elements like a hill or mountain that we use to orient ourselves in space.

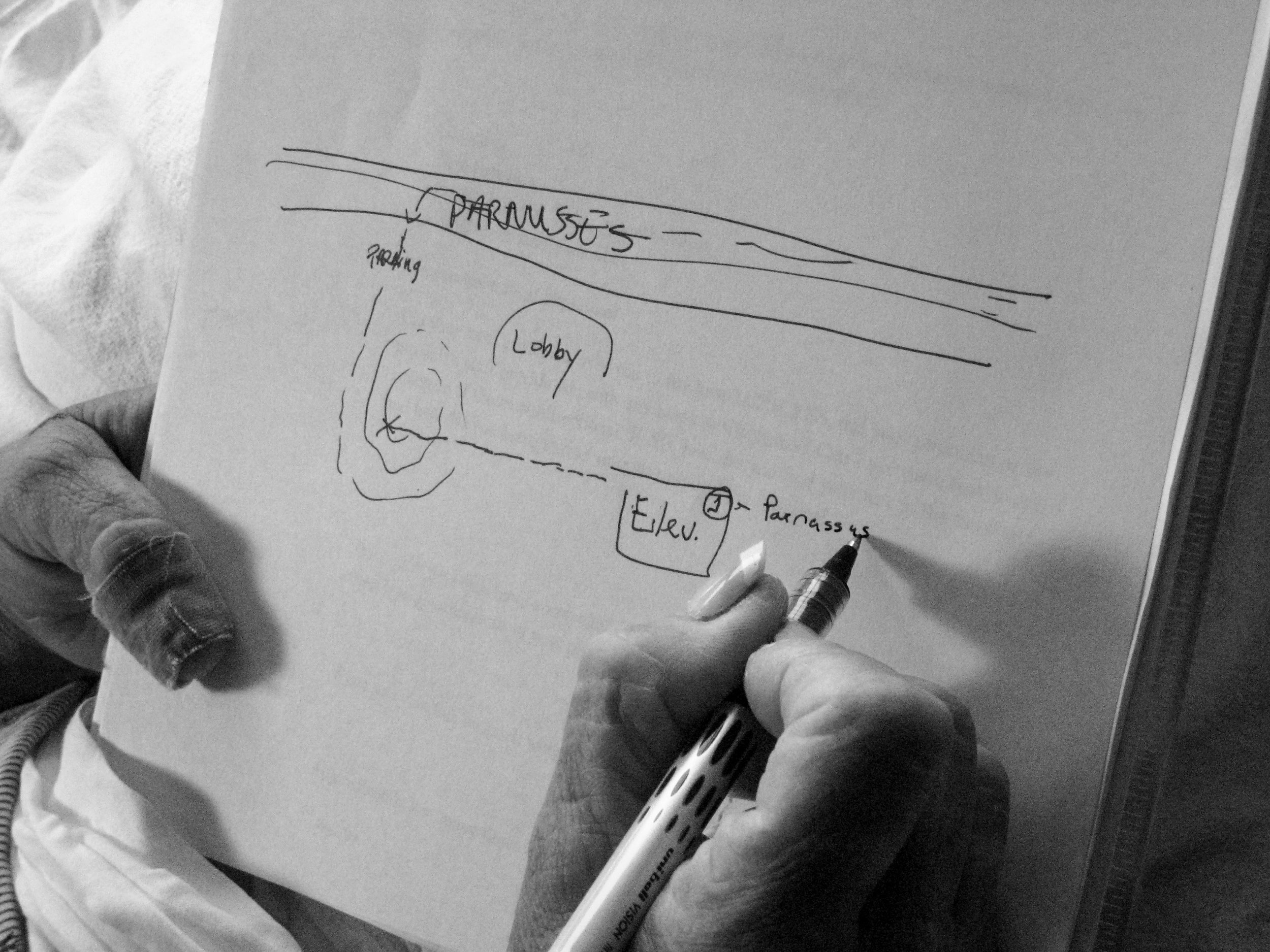

During the early 2000s when I was working in architecture we frequently applied both the design research methods and theories this little book produced (including the concept of “way-finding”, around which an entire practice and service offering would flourish). When designing navigation systems for hospitals we began our research by understanding what kind of working knowledge visitors had of the place. Where was the hospital located? Did they know where to park? How do they find their way to a particular clinic, then back? Our teams asked patients, visitors, and staff to visualize their routes. After the typical warning that they “aren’t good with directions”, people drew surprisingly detailed, accurate, and useful models like the one below by a recovering patient sketched in a few minutes time from her hospital bed.

Our research validated much of what Lynch discovered and informed the basis of a wayfinding logic that draws upon the recognizability and memorability that pathways and landmarks afford. This logic, in turn, supported a larger strategic offering we developed called Integrated Wayfinding Solutions that includes front-of-house and back-of-house tools and was implemented for hospitals across the U.S., including M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.