We tell stories to understand and express who we are, aspire to what we want to be, and shape what others think about us. We tell stories to entertain, mythologize, or just share. The many approaches to storytelling are a frequent topic at SXSWi this year, with 100+ panels that reference stories or storytelling. Our own story is being created every day, through conversations with our self, through interactions with other people, social networks, companies, and institutions. These days, we don’t have full control over it–online networks and digital communities are actively shaping, telling, and retelling stories about us and our behaviors that we’re not always aware of.

At SXSWi, the popular author John Hagel raised the distinction between stories and narratives. Stories are finite. They have a beginning and end. Stories are also about someone or something else. They are not personal to the individual. Narratives are open ended, with a resolution that is undefined. Narratives are personal and contain an invitation for others to participate in the resolution.

How can the story of our health turn into a narrative with friends, family, physicians and the care community that is coherent, useful, participatory, and evolving? How can narrative put a face on our conditions and enable deeper understandings of ourselves and more meaningful interactions between us, our caregivers, and health providers that help us feel better and lead to wellness?

A Story From The Field

“You know, nobody has ever really asked me to tell them how I got sick. They just want to know what’s wrong today.”

This sentiment was expressed by over 20 chronically ill patients and caregivers during a recent project for a healthcare client. We were tasked with understanding the journey they took as they tried to navigate their way to health and wellness, which some believed to be a state beyond their reach. We visited with people in their homes or over coffee and, after getting to know them a bit, asked them to tell us about their illness.

To our surprise, they often began at childhood, following an arc from innocence and health, to happiness and vitality, an on to their current chronically ill condition. Patients described a joyous and active youth when their bodies were strong and minds were clear. They followed that chapter with a turning point—a shattered ankle, broken relationship, or job loss—that led to their condition today. They also recalled the endless amount of times that they’ve had to explain who they were, what they thought was wrong with them, and the status of their treatment to armies of physicians, pharmacists, and insurance providers, starting from scratch again and again. And, after many of these conversations, they often felt as if they had taken two steps back emotionally and only one step towards getting better.

A Model for Building A Coherent Narrative

“Evidence strongly suggests that humans in all cultures come to cast their own identity in some sort of narrative form. We are inveterate storytellers.”

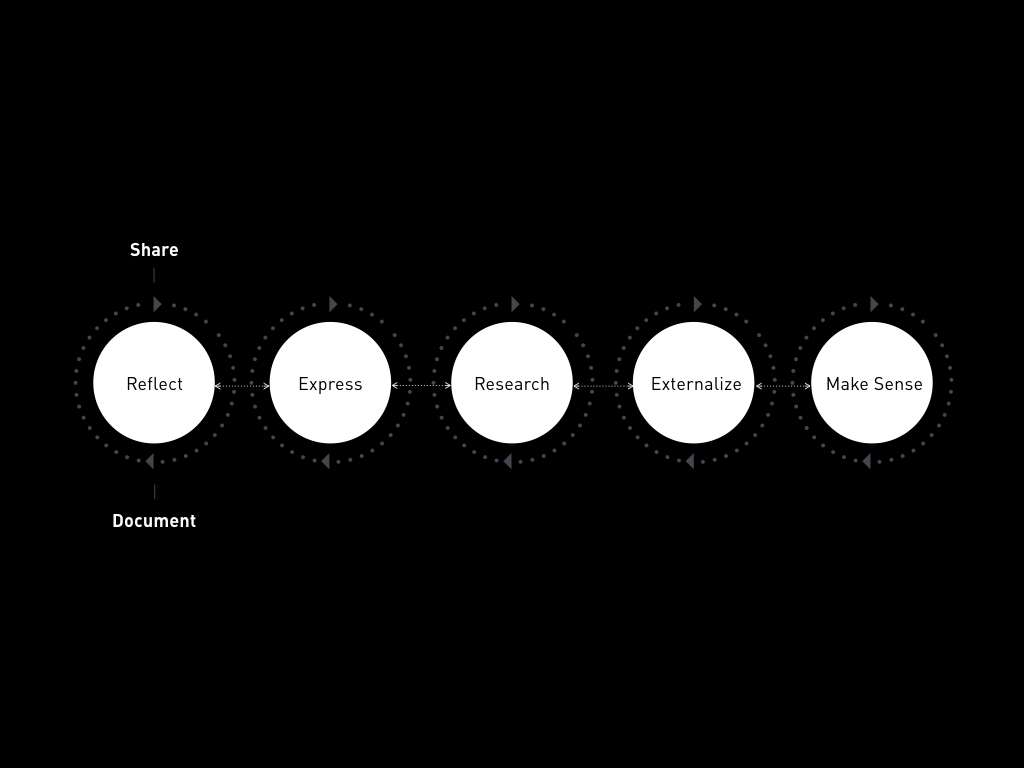

That project and others like it inspire a model of how health narratives could be built between patients, caregivers, physicians, and the larger care community. The model outlines some methods, and suggests resources, for helping these groups tell effective and meaningful narratives to each other. There are six activities in it for narrative building, and, despite their ordered structure they may not always unfold in linear fashion. Two overarching behaviors, “Share” and “Document” are constants whose frequency varies across the narrative-building process:

- Reflect: Think about your health, recall facts and events, begin a narrative

- Express: Tell someone, such as a family member or doctor, about a health problem

- Research: Search, find, and collect information about your condition

- Externalize: Display information about you and your condition in your environment

- Make Sense: Put the pieces of your history and research together

Below, each activity in the model is described in more detail in order to bring to light the emotional and functional dynamics of the patient, caregiver, and physician—three core actors in the health narrative.

1. Reflect

During Reflection, the patient or caregiver thinks about how they currently feel, how they used to feel, and what happened that caused their condition. They typically have an objective mindset as they try to recall facts. They may or may not write things down, and sometimes the detail is a byproduct of another communication with a family member or friend. Reflection may occur for them on-the-go, and through indirect storytelling or sharing, which may include small milestones, such as an athletic achievement or other performance, in addition to their health condition.

The physician may play a limited role during Reflection, encouraging and inspiring the patient or caregiver to think broadly about their life and condition by “starting from the beginning,” whether that includes childhood or the moment they noticed something didn’t feel right.

2. Express

Expression can be a more emotional state for the patient or caregiver because they are beyond the threshold of thinking about facts and begin to express how they feel about their condition (and they’re anxious to know more). They feel good talking out loud about what’s going on and sharing tentative plans about immediate next steps or the future.

During Expression, the physician is a sounding board. Patience and listening skills are necessary. While in consult, a calm tone of voice and body language can send a message to the patient and caregiver that it’s okay to talk about and share how they feel. It’s also a time for the physician to jot notes about the exchange and begin building a documented history of the emotional and physical state of the patient. This information can inform an appropriate point of entry for the next appointment, a nuance that lets the patient and caregiver know they’ve been heard and a tactic that saves time and energy for all parties involved in the care process.

3. Research

If Reflection and Expression occur previously, Research can be focused and a better use of time by the patient or caregiver because they can find more relevant information and actually build their knowledge. Their challenge is to strike a balance between a glut of related information and the right stuff to zero in on and obtain. Serendipity can play a role in their research as well—patients and caregivers aren’t always seated in front of the computer with undivided attention. Feeds and tools that help people make decisions about health and wellness, or collect data and discover new resources on-the-go, are needed.

The physician and staff can play an important collaborative role during this activity by guiding the patient and caregiver through mountains of information and helping them understand how to consume and use it. Taking the controls of a digital tool or set of resources and curating a packaged and prioritized set of content for the patient and caregiver to review and archive would be immensely helpful.

4. Externalize

Externalization is a discreet part of the process of building a coherent narrative. In his own work with the practice of “Narrative Therapy”, Psychotherapist Michael White describes the process of externalizing a patient’s thoughts, feelings, and life events to expose and define the problem they’re dealing with. This disengagement and eventual re-engagement helps people reconsider their relationship with their problem and look at it with a fresh perspective.

Externalization by the patient and caregiver can include the visual display and organization of verbalized narrative, written information, professional or institutional research and documentation, photographs, doodles, calendars, schedules, reminders, and ad-hoc tools created to improve their adherence to therapeutic regimens.

Physicians may enter into the externalization process and advance the narrative, and often add to an already overwhelming amount of information at the feet of the patient and caregiver. Curation is essential. Knowing what patients have or don’t have, and what caregivers understand or don’t understand is a must. Physicians may play the role of “can opener” - getting the patient or caregiver to verbalize their thoughts and feelings, help them see their own developing narrative in an objective light, and facilitate the disengagement and reengagement with their story. One participatory technique that designers often use called “journey mapping” can unpack and visualize a history of care and therapy for the patient and caregiver in an illustrated timeline. During this process, the physician, patient, and caregiver may co-create an actual map of their journey through health, sickness, therapy, and wellness.

5. Make Sense

“Sensemaking” is an ongoing activity and a priority for patients and caregivers on their path to health and wellness. But, often they don’t have the right information to act with or know what to actually do with all the data they are collecting. Making sense of a lot of stuff can feel disorganized, overwhelming, and confusing. This is mainly the result of not externalizing stories, research, and other information in a way that reveals meaningful patterns in what is collected and created. Providing the patient and caregiver with instruction about what and how to externalize their information can reduce the anxiety inherent in dealing with piles of forms, facts, figures, communications, and other content. Giving them ideas about how to connect the dots in all this content can produce an enlightened understanding of their own behavior and health.

Physicians often add to the piles of information that need to be externalized without an accurate picture of the stack. They need methods and tools that enable them to help the patient prioritize their information, make connections, and give them the ability to intelligently and meaningfully organize their commentary, history, advice, and therapies.

Sensemaking, the act of “forming associations and connections between objective data, sensory experiences, and personal knowledge,” is one of the most complex activities and largest unmet needs in the process of building an effective narrative between patients, caregivers, and their healthcare ecosystem.

Packaging, Publishing, and Sharing the Narrative

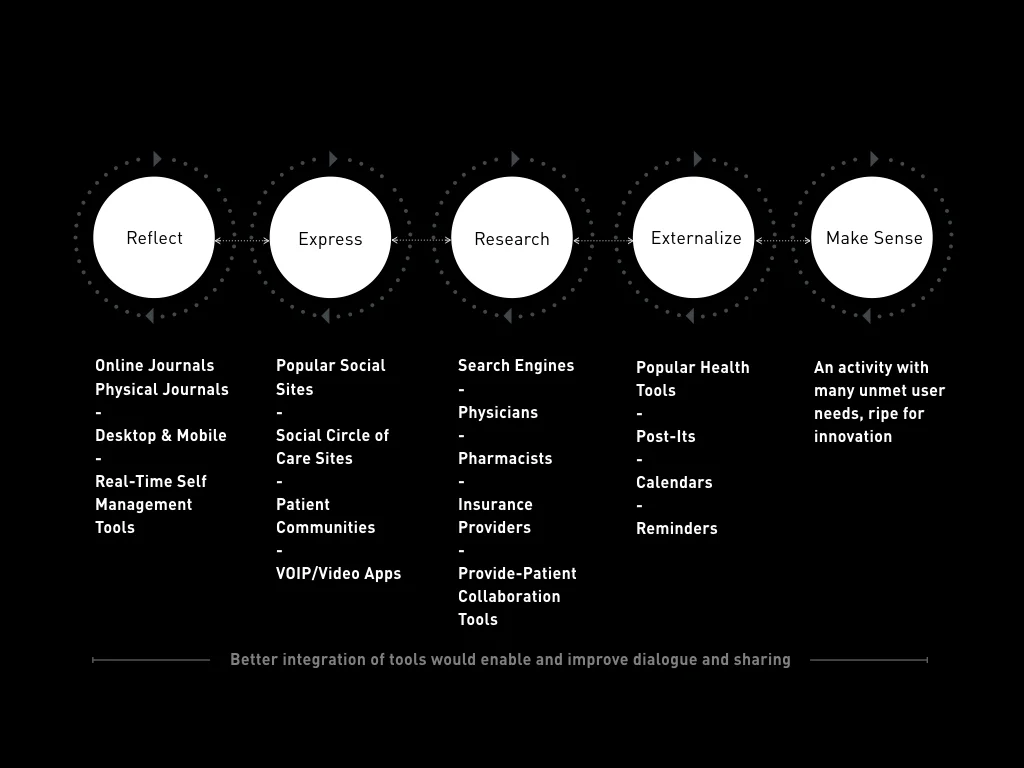

The activities within the narrative-building model describe behaviors and techniques for storytelling, but how can patients, caregivers, and physicians actually make a living document of health that is easy to create, edit, access, and share? Many popular tools, applications, and connected care technologies offer ideas and possible solutions. Let’s look at some of them.

Facebook, Twitter, personal blogs, and other kinds of physical journals are common tools that people use to reflect upon, publish, and catalog life events. Evernote, a note-taking application, has a robust product platform with desktop, mobile, and tablet offerings and the ability to “clip” content from websites. Archiving and sharing with this app is easy. And, Evernote’s new partnership with Moleskine, the legendary journal company, enables people to capture, upload, tag, and search visually-optimized handwritten notes, ideas, and reminders. Real-time self-management and awareness devices such as Nike+, Proteus, and Shine, which generate daily behavioral data, are becoming more mainstream. These digital technologies can complement and support the everyday file folders, binders, bags, and boxes that often collect paperwork from all members of the healthcare ecosystem.

Google Docs and Google Drive offer easy-to-reach documentation and storage solutions for many different types of information. Their web-based nature makes online research a natural part of the workflow. An integrated “Research” functionality enables users to highlight content, begin a contextual search, and with a click of a button results appear in a sidebar and users can follow search results to more data-rich websites and online documents. VOIP (Voice Over Internet Protocol) and video services like Skype, Google Voice, and Facebook Chat connect patients with caregivers, physicians and others in their healthcare community. Sites and applications like Duet Health enable hospitals, pharmacies, and other health service providers to work more closely together to educate and manage care. And services such as Patients Like Me, Tyze, and CaringBridge go a step further by providing ample contexts of health histories, treatments, and logistics.

Also, picture-based web bulletin boards such as Pinterest feature crowd-sourced, shareable imagery. While privacy and security are concerns in a site like this (as they are with all the previously mentioned solutions), it nevertheless provides a model for creating visually rich social media that reflect the visual characteristics of healthcare documentation, records, files, and scans.

Adding a row of existing resources like those mentioned above across the health narrative model suggests opportunities for innovation through a tighter integration of tools, services, and activities.

Solutions that help patients and their care community confidently externalize their narratives and make sense of an ongoing narrative are generally lacking in the market. Externalization and sensemaking are two of the most difficult yet important activities in the narrative model and may contribute greatly towards achieving coherent communications and adherent regimens. Major healthcare institutions, pharmacies, insurance providers, employers, and startups all have a role to play helping to build these meaningful and actionable health narratives between patients, caregivers, physicians, and the broader ecosystem at large. Who will master the evolving art, science, mechanics, and logistics of storytelling in today’s age and enable journeys to health and wellness?