In The Camera Fiend, Bill Jay traces a quick history of the technical, social, and cultural histories of amateur photography, revealing the contentious relationships that have always be present between photographer and human subjects. I felt this discomfort during certain moments of my Aunt’s funeral services as a participant-observer-photographer.

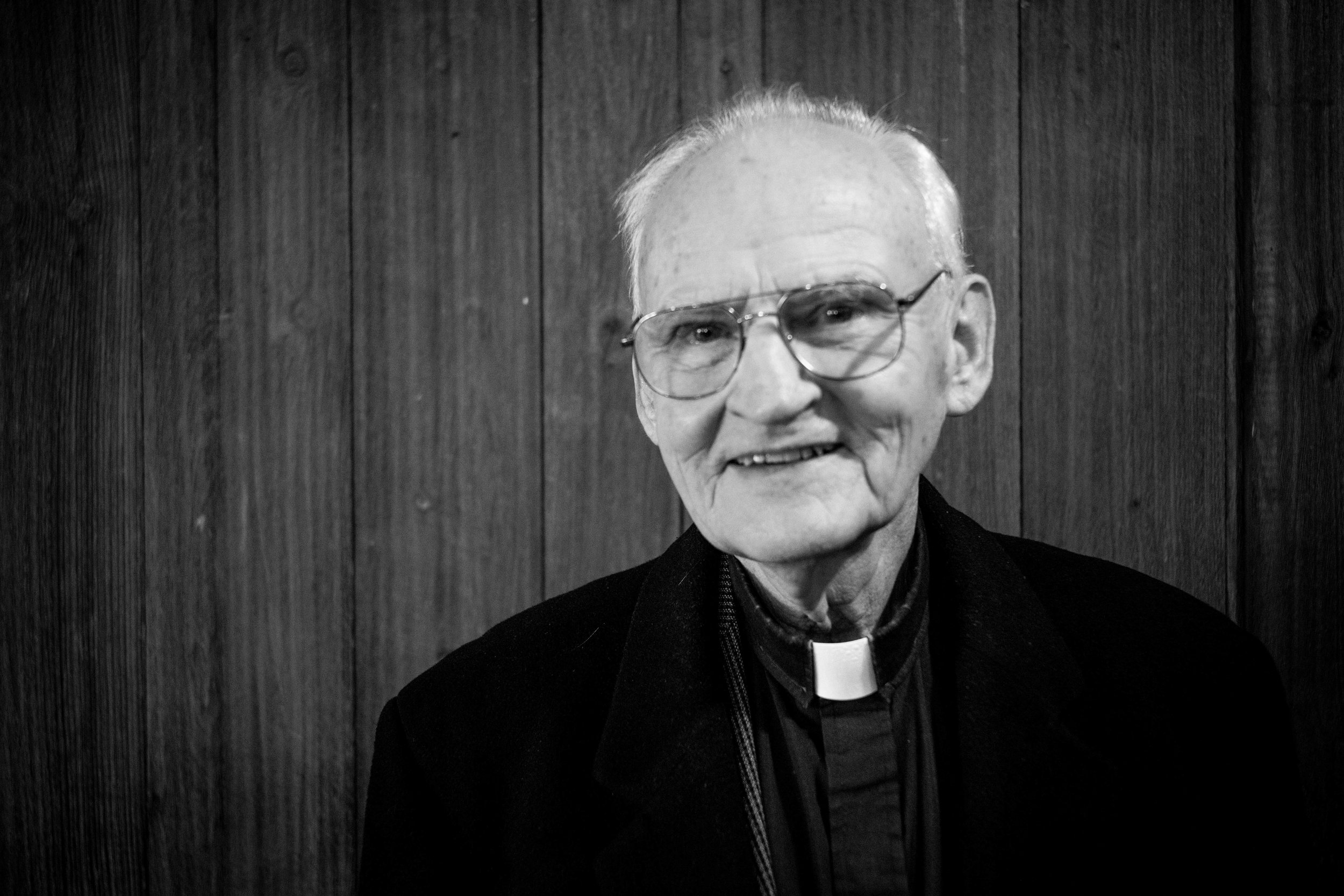

“Are you bringing your camera?” My instinct said “no” but there was a dutiful intent behind the question that my mother asked me before going to my Aunt’s wake. Catholic funerals, like First Holy Communions and all other apostolic rites of passage, are extremely physical events. Their physicality is designed to be cathartic and memorable. And they are. My first was at 10 years old, my grandfather (my Mom and Aunt’s father) had passed while in his 70s and I recall the slow march to view his body. The others prayed and looked intently at him, then exited left, revealing his state all-of-a-sudden to me: gaunt, drawn, gray, and vaguely recognizable, an image as clear to me today as it was three decades ago. Death carries a distinct look that makes a lasting impression.

Here I was, again, at Laskowski Funeral Home where generations of my family have been laid to rest in a traditional Polish-Catholic way: an open casket viewing on day one that hosts a steady stream of respectful family, friends, and acquaintances most of whom comment on the look of the deceased; and, a memorial Mass on day two that is bookended by journeys from the funeral home to the church, then to the cemetery. Somber, ceremonial, and social, you leave taxed but feeling secure in the company of family who talk about old times with your loved one, or catch up on those they’ve missed.

Aunt Chris was our favorite Aunt. Never married, she lived a full life always busy with something. She loved hockey – as a kid, I traded turns attending some rather tough minor league games with my brother and cousins on her season’s tickets. She loved cocker spaniels, owning three that I can remember, all of them high strung and not exactly nice; one of whom died in a terrible accident after Christmas Eve dinner (always hosted by Gram and Aunt Chris). She could bake – a mix of customary and Polish pastries done just right. My mouth still waters thinking of them.

So, I brought my camera and I’m glad I did, though it was discomforting...for me, my family, and others. If my mother hadn’t prompted me, I wouldn’t have taken a single shot. I had to be encouraged, a state that is out of my character when holding a camera. “Are you gonna get this, Jon?” I snapped away and felt the communal cringe with each shutter clack. Many public moments are at least semi-private. We walk streets and make our way through social situations with a functional amount of self-regard intact. Amateur photography, though naturally invasive, is a widely accepted phenomena in everyday life, but not in death. There, it’s an intruder no matter what the intent may be and when it appears, some, understandably, recoil from the breach of privacy and custom, the crossing of a cultural threshold where family, church, and tradition commingle. It wasn’t until the post-Mass dinner that I felt I could achieve the permission and space to retreat that often come with documenting a communal moment. The necessarily upbeat tenor of the crowd, the old but distant relationships, the sheer number of people crammed into a classic Northeastern diner on a sharp January day...all factored in to a rather perfect photo opportunity, including one that I’m in.

Thanks for the nudge, Mom. And, yeah, she looks good.